Background to the Jukskei River

-

Running under the city of Johannesburg for many blocks, the Jukskei River first sees daylight in Bertrams, a deprived neighbourhood with high unemployment, poor services, large migrant communities, and limited economic opportunity. The waters then run in concrete culverts above and below ground through semi-industrial areas before joining a neglected green corridor that stretches through Bruma. From there, the river turns north east to flow, gathering pace, trash and flooding potential, though communities both very poor (for example, Alexandra, the oldest township in the city) and very rich (for example, golf estates such as Dainfern and Steyn City), past those who have chosen to surround themselves with security walls and those forcibly incarcerated (Leeuwkop Prison also sits on its banks), and traversing the increasingly less built up quasi-farmlands of Lanseria, it’s water carrying with it smells, toxins, litter and other jetsam, before it merges with the Crocodile River around 50 kilometres away from greater Johannesburg to spill into the Hartebeespoort Dam. The path of the river along its meandering route, portrays the material conditions of diverse socio-economic layers of the city, as well as the complex social relationships that continue to define Johannesburg life.

The following layout is comprised of an edited extract of the late architect and activist Marion P Laserson’s 2018 research report, Renovation of the Jukskei River Canal in Bertrams, Lorentzville, Judith’s Paarl to Bezuidenhout Valley, with notes added by the late Paul Fairall, founder of the Jukskei Rejuvenation Project: Water for the Future’s predecessor.

Ancient to Modern History: the story of abundance and lack

Mountain Sanctuary Park, Magaliesburg by Jacob Knight for Shoshong

Paul Fairall: The Magaliesberg is one of the oldest mountain ranges in the world, as is the upper catchment of the Jukskei and Crocodile Rivers one of the oldest in the world. The Jukskei/Crocodile Rivers were likely both Stone- and Iron-age highways. This scenario has been constructed from a number of sources: excavations at the boulders in Midrand, the research by Wits University into the heritage caves of Glenferness on the banks of the Jukskei River in the late 1940’s, and remnants of fire kilns on Linksfield Ridge, Melville Koppies and the Lonehill Tor. Research shows that humans lived near both rivers 14,000 years ago. When and why they left, however, is unknown.

‘The forefathers and mothers of the Batswana and the Bapedi people settled here again 2,000 years ago. Homelands stretched from the wetland and abundant food sources of the Ridge they called Dinokeng - an Nguni word meaning “The Place of Waters” - over northern Johannesburg, through to what is Midrand and Fourways today, down the gorges and hillside slopes into the fertile Moot - an area between the Magalies (Cashane Mountains) and Johannesburg mountain ranges.

Considering the food security this population enjoyed, we can assume they lived more or less peacefully for nearly 1,900 years - until, over the course of the 1800s, four cataclysmic events took place.

The first was the Mfecane, (Zulu: “The Crushing”, Sotho: Difuqane): a series of Zulu and other Nguni tribal wars that forced migrations during the second and third decades of the 19th century, and changed the demographic, social, and political configuration of Southern Africa. The Mfecane was set in motion by the rise of the Zulu Military Kingdom under Shaka (c 1787-1828) who revolutionised Nguni warfare. The rise of Shaka’s kingdom, which took place during a time of drought and social unrest, was itself part of a wider process of state formation in South-Eastern Africa. During this time Mzilikazi Khumalo, Shaka’s top general, fled Zululand after a dispute over cattle numbers looted in battle and meant as a tribute to the King.

Antique engraving of a Tswana village, 1875. Artist unknown Source.

Queen Manthatisi, date & photographer unknown. Source.

Assimilating young maidens and boys as he crisscrossed the Highveld and settled at Hartbeespoort Dam, where the Jukskei and Crocodile Rivers converge. The remnants of his settlement are still visible today around the base of the cable car station.

Between 1827 and 1832, Mzilikazi built three military strongholds along the Magaliesberg, the largest being Kungwini, at Wonderboom, north of present-day Pretoria; Diananeni just north of present day Hartbeespoort Dam and Hlahlandela, near Rustenburg. Mzillikazi, a proven brilliant general knew that holding the high ground (The Magaliesberg Range) and having an ample food supply (TheMoot) were clear tactical advantages. He knew he had food security.

At the same time the warrior Queen Manthatisi gathered all the nomadic tribes on the central, western and northern areas of the Highveld together in a huge mass of people and animals that was not sustainable and imploded on itself. She was doomed to fail because there was no food security.

Sketch of Kokolo People, artist unknown. Source.

The third event was the arrival of the Voortrekkers from Natal over the Drankensberg and on to the Highveld from 1838 onwards. It was their guns and horse mounts that unseated Mzillikazi.

The fourth event was the discovery of the main conglomerate of gold on the farm Langlaagte in 1886. During the last year of the second Anglo/Boer 1899-1901; 8500 of the remaining 14,500 “Bittereinders” (unwilling to admit defeat) found sustenance in this fertile valley.’

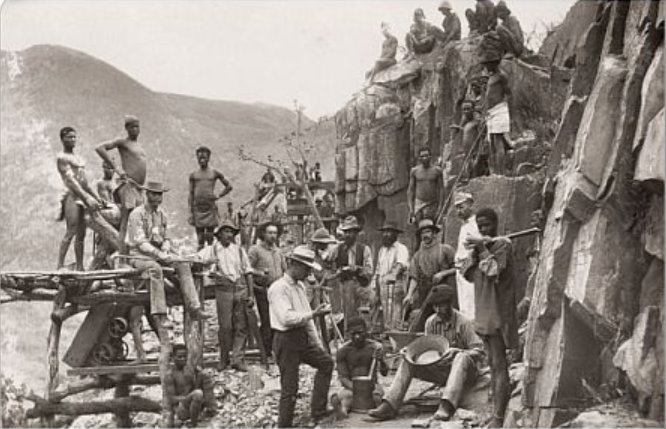

Laserson: ‘Johannesburg is unlike most other major cities in the world, those which are situated on the coast or on a substantial, navigable river. Instead , Johannesburg’s location was decided by the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886. Gold also informed the way in which the built environment of the city, with its farms, housing, mines, and mine dumps, was developed.

Republic Gold Mining Company, De Kaap Valley, South Africa, 1888. Photographer unknown. Source.

Historical and modern construction of the Jukskei River

Archives of Marion Laserson, 2018.

Because of gold, the importance of Johannesburg’s rivers is seldom acknowledged. But while the rivers are smaller than those of many other cities, our Highveld rainfall patterns tend to be heavy. There is a very short period of warning time – a few hours at most – about oncoming floods. People also tend to be more careful about building and occupying land close to big rivers and this is not the case with small rivers, which are often considered to be little more than storm water drainage channels. Johannesburg is characteristically constructed very close to the Jukskei river – often in its very flood plain. This leads to frequent damage to property and municipal infrastructure, and in extreme events, devastating loss of life.

In view of storm water, Johannesburg’s topography for run-off is unique. The city is built on a watershed running more or less east west, the Witwatersrand – freely translated as ‘white water ridge.’ Rain falling on the south of the ridge runs into the Klip River, the Vaal and Orange Rivers and into the Atlantic Ocean. Rain which falls on the north of this ridge, including the Jukskei River, eventually joins the Crocodile and the Limpopo Rivers and expels into the Indian Ocean.

Around 1840 the Voortrekkers arrived in the Transvaal and established farms. They seem to have found sufficient water for farming. Originally this came from the Natalspruit but, as the population increased, the Jukskei became an important source.

Water in the Natalspruit proved to be inadequate for the rapidly developing mining town. A study for the Johannesburg Planning Department (Argent & Green 1986) gives an account of how the Natalspruit, with the help of additional wells and dams, initially provided sufficient water for the mining reduction works, as well as for public buildings such as the hospital, gaol, a police station, and the diggers’ camp. But people who did not have direct access to a stream, spring, or well were obliged to buy water from carts at anything from threepence- to sixpence a small bucket, depending on how far the water had been carted. “The leaders of the community then looked to Farm Doornfontein’s other water source—the Jukskei River”(Argent & Green 1986 in Laserson).

By 1888, the population had grown to 3 000 and the first storage reservoir was constructed over one spring of the Jukskei, close to Joe Slovo Drive (then called Harrow Road) which is still in use today and has a capacity of 4,5 Ml.

Witpoortjie Falls, Walter Sisulu National Botanical Gardens. Source.

Archives of Marion Laserson, 2018.

Human settlements have a major influence on rivers. On January 1 1887 the Johannesburg Consolidated Investment Company established the township of Doornfontein. Soon Doornfontein’s sparsely vegetated veld—typical of the mining town—took on a parklike quality. Thousands of trees were planted and the suburb became the select neighbourhood of mining magnates and successful businessmen. Mansions were built with beautiful garden settings.

On the East of Doornfontein, Bertrams, Lorentzville and Judith’s Paarl were developed. Bertrams was established on 1 January 1889 by Robert Fuller Bertram, a successful stockbroker, and Norwich Union Life Insurance Society, the township owner. In partnership with H. Lorentz, Bertram established Lorentzville on 1 January 1892. Both of these suburbs were considered to be “out in the country” and property owners bought up the groups of small stands and developed orchards, vegetable gardens and horse paddocks.

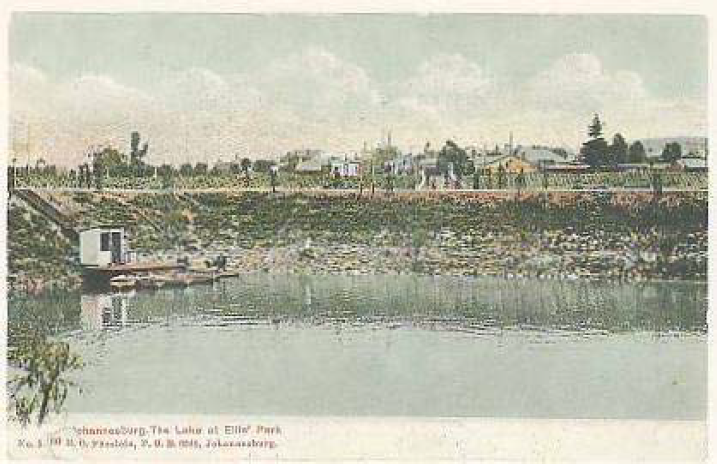

But much of the area was swampy and mushy and facilitated the construction of the lake at Ellis Park. In 1905 the Council named this area as Ellis Park in honour of J.D. Ellis, Chairman of the Parks and Estates Committee. This eye of the Jukskei at Ellis Park was fitted with pipes to supply the town in June 1888. The uncovered lake had a capacity of 98 Ml. In Watershed Town—The History of the Johannesburg City Engineer’s Department it is recorded that by the end of 1894 more reservoirs were constructed, the largest at Ellis Park on the site of the tennis courts.

Despite these dams and reservoirs the demand for water exceeded the supply. In 1901 the Town Council of Johannesburg was appointed and this facilitated the formation of the Rand Water Board which, in 1905, took over the assets of the water supply system and the water supply was then greatly improved. By 1925, the major portion of water supply was pumped into the reservoirs at Yeoville, Brixton and Berea. It is assumed that the spring water under Ellis Park is now carried away by the Jukskei River and in addition to storm water and sewerage, comprises the main body of the river water.

Archives of Marion Laserson, 2018.

Of the river: storm water and sewerage in Johannesburg

The Jukskei storm water and sewerage tunnel, by Sean Christie, 2001. TimesLive

Johannesburg’s swerage and storm water drainage follow the channels of the Jukskei and Klip Rivers as they flow from the Witwatersrand Ridge. In May 1903, it is recorded in the Minutes of the Johannesburg Town Council that the Medical Officer of Health and the Town Engineer recommended the abandonment of the bucket system in favour of a system of water borne sewage-called a “gravitation water-carriage system of sewerage” .

It was noted “that the lines followed in the drainage scheme are determined by the conformation of the ground.” It was recognized that the ridge separated the north from the south drainage schemes. The Southern drainage scheme was divided into the east and west systems roughly divided by Hospital Hill and von Brandis Street to the municipal boundary. The Eastern rainfall drains eastwards into the Natal Spruit and the Jukskei River.

The Council resolution of 10 September 1902 resolved that although surface water and sewage should be treated separately, “the systems must be dealt with together because it would be economical to lay both channels in the same cutting, placing the sewers on the one side of the surface water drains, but at a somewhat lower level.”

It was also suggested that “Generally speaking, except where spruits in other situations already exist, the storm water drains will be lain in the streets…” It was also recommended that “as the maximum flow occurs only for short periods, and at infrequent intervals, its erosive effect is not nearly so serious as it would be if the flow were constant. As these channels have to pass considerable volumes of water, it is desirable to obtain a high velocity of flow so that the section may be as much as possible reduced.”

Wendy Bodman, in The North Flowing Rivers of the Central Witwatersrand 1975 to 1981, mentions a phenomenon specific to the Jukskei River. She says: “On the Witwatersrand, urban streams became degraded because expediency and a need to control Highveld summer storms led to the use of water-courses as drains to carry ’away’ storm water. In countries with a more uniform spread of annual rainfall, this storm water is first piped via sewers to sewage purification plants, where, after it is de-littered and purified, it is returned to the river system (the ‘combined system’)”.

The Jukskei River at Alexandra Township, photo by Angus Begg, 2021. Daily Maverick

*Laserson’s detailed summary is the product of thorough research drawing from a wide range of sources: “books, documentation, university studies, records of the Johannesburg City Council and the City Engineer’s Department as well as personal research”, while Paul Fairall’s additions involve specific details about the early history of the area. The website writer has re-structured the report for the purposes of providing an accessible narrative but interested readers can download the full report here.